Even the drama's most sympathetic character, Milan (Dragan Bjelogrlic), refuses to let his wounds stop cultural enmity.

#Lepa sela lepo gore tunel movie

Brutally frank about its own culture, the movie refuses to follow the rah-rah party line. But it shows Serbs burning villages (hence the title), shelling towns and demonstrating systemic disregard for their enemies. This is not to say that "Pretty Village" is littered with bodies in unmarked graves or the horrifying Nazi-style atrocities conducted on all sides. Given the filmmaker's nationality, it's astonishingly candid about Serbian involvement in the horrors of the war. It also embraces the new American cinema, the blood-and-guts, laugh-all-the-way-to-hell storytelling of Oliver Stone and Quentin Tarantino. But the movie, which was scrimped together and shot despite the ravages of war, is anti-war and humanistic. It's loaded down with flashbacks, symbolism, surrealism, anti-communist satire and almost-gratuitous lapses into music (no European film can escape without music, it seems).

#Lepa sela lepo gore tunel full

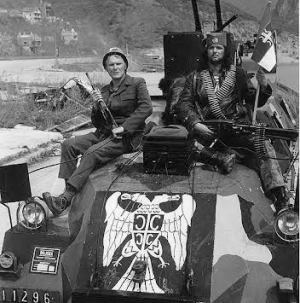

Srdjan Dragojevic's film is full of the elements you'd expect in an Eastern European film. But one of the most remarkable is "Pretty Village, Pretty Flame" ("Lepa Sela, Lepo Gore"), a Serbian-made movie in which the members of a Serbian patrol and an American journalist find themselves trapped in a tunnel besieged by Muslim militiamen. With nothing to do but wait for death, the trapped soldiers amuse themselves by staging allegorical circus acts.FILMS ABOUT the Serbo-Croatian-Muslim conflict have been surprisingly few and far between. Later in the film, it will become the scene of horror when Serbian soldiers are trapped by Muslims within. The film opens with a shot of European and American dignitaries smiling broadly as they inaugurate the new Brotherhood and Unity tunnel that links Zagreb and Belgrade. Meanwhile, a beautiful American journalist is captured by the Serbs. The story moves to 1992 and begins as the war between the Serbs and the Muslim ignites in horrible violence and the friends find themselves forced into becoming enemies. Though curious, the boys were too frightened by the mythical boy-eating ogres said to venture within. While growing up during the ’80s, the two often hung out near an abandoned tunnel. Set in Bosnia during 19 (like a pendulum, the time frame swings back and forth), and allegedly based upon a true story, the plot focuses upon the longtime friendship of Muslim Halil, and Serbian Milan. Though cloaked in explosive black humor, the serious anti-war message of this bitterly satirical and politically charged Yugoslav film cuts like shrapnel. Through flashbacks that describe the pre-war lives of each trapped soldier, the film describes life in pre-war Yugoslavia and tries to give a view as to why former neighbours and friends turned on each other.įollowing the success of the movie, Bulić wrote a novel named Tunel that’s essentially an expanded version of his magazine article. The film’s screenplay is based on an article written by Vanja Bulić for Duga magazine about the actual event. The plot, inspired by real life events that took place in the opening stages of the Bosnian War, tells a story about small group of Serb soldiers trapped in a tunnel by a Bosniak force. Twelve years later, during the Bosnian civil war, Milan, who is trapped in the tunnel with his troop, and Halil, find themselves on opposing sides, fatefully heading toward confrontation. They never dare go inside, as they believe an ogre resides there. Two young boys, Halil, a Muslim, and Milan, a Serb, have grown up together near a deserted tunnel linking the Yugoslav cities of Belgrade and Zagreb.

In the hospital they remember their youth and the war. At the Belgrade army hospital, casualties of Bosnian civil war are treated.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)